The pandemic could herald a paradigm shift in our conception of value, freeing us to imagine new models that can scale and sustain cultural and creative activity.

The past few years have changed us: through grief and isolation and fear and uncertainty – and through finding hope and possibility and resilience and clarity about what we love. Creative industries have provided humour and insight, captured the unimaginable and been a source of both distraction and focus, reminding us of who we are and how we are connected.

And, for all their collective talent, creativity, entrepreneurial spirit and resourcefulness, creative industries have been profoundly affected by the pandemic. Industries that play a vital role in giving expression to our experience, in which we find purpose and meaning, have reached a point of true crisis in the context of a point of true crisis. Many are simply unable to continue to work within prevailing models. However, this very crisis could place creative industries at the vanguard of a paradigm shift that revolutionises our conception of value, out of which could emerge more sustainable models for the future.

This idea is powerfully expressed by Arundhati Roy: the pandemic as a portal.

‘Historically, pandemics have forced humans to break with the past and imagine their world anew. This one is no different. It is a portal, a gateway between one world and the next. We can choose to walk through it, dragging the carcasses of our prejudice and hatred, our avarice, our data banks and dead ideas, our dead rivers and smoky skies behind us. Or we can walk through lightly, with little luggage, ready to imagine another world. And ready to fight for it.’

What kind of world can we imagine; what future for ourselves, our children and those who come after them? What creative industries participate in reshaping how we see, understand and engage with this change, for their future osemand ours? How will they?

True paradigm shifts, as illuminated by philosopher Thomas Kuhn, occur when there is sufficient new information and insight to challenge and disrupt prevailing assumptions that no longer hold true and enable models already under stress to give way to new models. The shifts gain momentum when the prevailing models no longer fit the realities. It is precisely when the problems are large and complex and urgent that we can look beyond even the problems themselves to the new models (the paradigm) needed to solve them.

Creative industries can enliven understanding of what is needed and how to move forward and connect people to an inspiring vision grounded in a more dynamic concept of value

Even before the pandemic, new information was challenging our assumptions about value. Specifically, the notion that we can conceive of value, even economic value, in purely financial terms has been facing existential questions. Research by economists from Michael Porter to Joseph Stiglitz to Thomas Piketty and Kate Raworth has underscored the major insight in modern economics that we have misaligned social, cultural, environmental and economic factors.

Marianna Mazzucato has advocated for value as ‘a goal which can be used to shape markets’. Jed Emerson has provided insights over decades on blended value, reflecting how purely financial and economic dimensions fall short of recognising what creates value and interrogating the purpose of capital. Emerson wrote recently that the transformative potential is to ‘make a direct connection between the investment of our capital and the creation of a material change in our communities and ecosystems’.

This more dynamic and integrated conception of value has informed developments such as purpose-driven business and stakeholder capitalism, and other approaches recognising the value of social, cultural and environmental impacts as well as financial performance. The development of impact investing as a field – and its broader influence evident in wider markets – is driving integration of positive social, cultural and environmental benefits with financial measures at the centre of performance.

The effects of these macro shifts are profound. Applied to the creative industries they hold levers to break through the paradox that ‘the problem of value in arts and culture is usually perceived to lie with arts and culture, not with the concept of value’. The impact of this could be Copernican in its repercussions for how we think about value and its relationship to the economy.

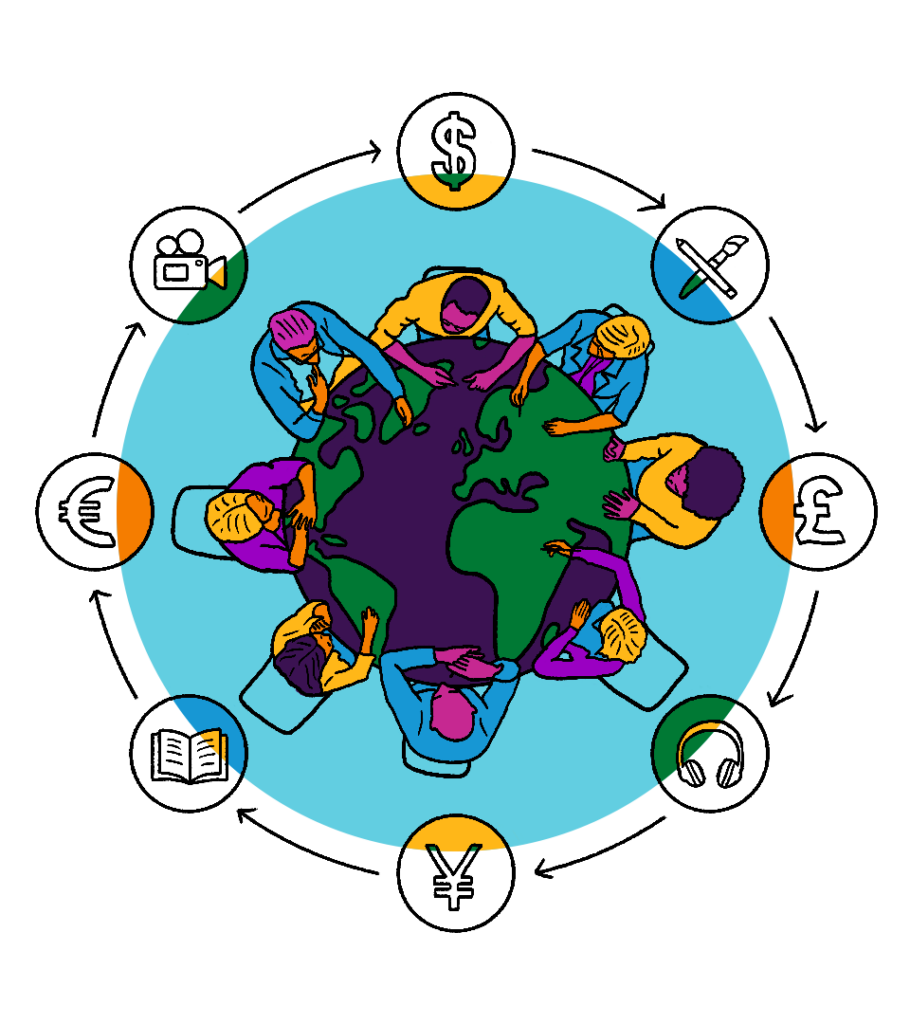

The creative industries can be emblematic of a broader, more dynamic and multi-faceted conception of value. They stand as beacons of the ways in which (non-financial) value is often left on the table. The creative economy encompasses a kaleidoscope of enterprises, from fashion to social media, hospitality, live entertainment and creative spaces. Collectively, the creative industries have the capacity to shape the way we see positive and negative impacts in our lives. Some, such as fashion and hospitality, have provided a focal point where sustainability and human rights meet supply chains and consumer demand. Some remind us of who we are and where we came from, influential in connecting hearts and minds to issues: songs and memes and games give expression to community sentiment and bring people together more effectively than politics and laws and even science.

These industries already have a storied history of creativity and innovation, including in the way they work. Arts-based and creative enterprises were early adopters of mission-driven business and demonstrated where commercial revenue models, governments and donor funds could be brought together in complementary ways. Dance, orchestral music, museums, galleries and opera all provide examples of business models that utilised intentional design for cultural benefit as well as to enable the ongoing cultural endeavour at their centre.

As impact investing developed, arts organisations and impact investors came together in experiments in how finance can be better utilised in the toolkit of innovative solutions. Triodos Bank has a long track record of financing arts organisations, based on the belief that ‘they contribute to society by connecting ideas and people, and reflecting, stimulating and encouraging positive change’. For example, the bank financed a leading choreographer in Brussels to develop a world class studio, which reached increasing numbers of students with dance and developed a valuable cultural institution in the community. The Australian Chamber Orchestra Instrument Fund enabled the orchestra to develop what’s billed as the greatest golden age collection of instruments in the world, attracting talent and providing a competitive edge for musicians and a unique experience for audiences.

There is much to learn from what has already been tried and tested, but it is not yet a complete answer. Funding and financing models for public goods and areas of creative endeavour have been under stress for a long time. This is the result of a confluence of market dynamics, policy settings and changing context. The pandemic did not originate the resource stress; it removed any doubt that the old models are in crisis.

Paradigms gain their status because they are more successful than the alternatives in solving a few problems that the group of practitioners have come to recognise as acute. In their 2021 research article ‘From public good to public value: Arts and culture in a time of crisis’, Julian Meyrick and Tulla Barnett observed:

‘Instability creates a disorientation hard to bear, even as it offers unlooked-for opportunities to revise what existing knowledge comprises. The old understanding and the new, which Kuhn sees as distributed between two distinct groups, may be internalised as a dilemma within one community and set of practices[…] Inevitably culture, as the pre-eminent symbolic domain, will be a vehicle for this, and crisis will make use of culture as different understandings struggle for paradigmatic ascendency.’

Shaping new models that can scale, replicate and sustain cultural and creative activity will require strategic leadership and commitment, innovative thinking and experimentation, building practice, and imagining, and re-imagining, to create viable models. This will require us to look beyond contests between public and private and take a more holistic approach. New bargains will need to be struck that place different sectors and actors as key collaborators in expanding and enhancing value and increasing economic activity. The available assets and levers within the creative industries will also need to be considered afresh to identify and optimise the opportunities for cultural and creative organisations to think about their resources differently. One foundation stone for this will be for cultural institutions to invest more in, and aligned with, their mission and values – even using their balance sheets to support and enhance the collective. It is high time to move past unhelpful and polarising assumptions and shape a new paradigm.

As well as providing fertile ground for paradigm shifts, creative industries hold up a mirror to our assumptions and what is at stake. What if energy and passion are not harnessed with clear and common purpose to sustain our culture and the means of its expression? What if there is not sufficient focus and leadership to reimagine the models to support vibrant and unique creative industries and preserve and celebrate local cultural heritage and give expression to our experience?

Leaders including Upstart Co-lab and its partners are already signalling disruption to some long- held assumptions about value. Their focus on ‘how creativity is funded by connecting impact investing to the creative economy’ is putting culture and value in frame and explicitly questioning current models. Bold experiments such as NFTs are entering the picture: at worst, these could be a dilution of what is considered valuable; at best, they could revolutionise the way value is ascribed, maintain the links between artists and the value they create, and enable new dynamic ways of engaging with and financing creative endeavour.

A concerted, energetic response that makes arts and culture a priority could deliver significant benefit for communities and society and for the economy; a failure to answer the call will be a unique opportunity missed. The leadership and initiative demonstrated in this collection are vital to placing creative economies squarely in the context of value for sustainable development and sparking dialogue, insight and ideation to mobilise more people and organisations and move with the speed and efficacy the times require and the issues deserve.

I am immensely grateful to have been invited by the collaborating partners, Upstart Co-Lab, Nesta Arts & Culture Finance and Fundación Compromiso, to contribute to this collection on Creativity, Culture & Capital.

New models can transform outcomes for communities and enrich and make sustainable the potential of creativity and innovation. Creative industries can enliven understanding of what is needed and how to move forward and connect people to an inspiring vision grounded in a more dynamic conception of value. Funders and financiers, policymakers and innovators who join with them will play a vital role in giving that vision form and function – and showing many in the creative industries and beyond how a culturally rich and economically prosperous future can take shape.