An art-science collaboration aims to learn more about the ‘wild diversity’ in the ways in which we experience the world.

You open your eyes and a world appears. What could be simpler than that? It may seem as though the world – with all its colours and shapes, people and places – just pours itself into your mind through the transparent windows of your senses. And that the self – your self – is perched somewhere behind your eyes, taking in a river of information and figuring out what to do.

But how things seem is not how they are. The apparently simple act of experiencing a world is a remarkable feat of biology – an everyday miracle, which nature has specifically designed us to not recognise as being so.

Imagine for a moment that you are your brain. There you are, locked in the bony vault of the skull, trying to figure out what’s out there in the world. All you’ve got to go on is a constant barrage of sensory signals that are only indirectly related to what’s out there. These signals don’t come with labels (‘I’m from a cat! I’m from a cup of tea!’), and their inherent ambiguity means that perception – the process of figuring out what’s there – cannot simply be a ‘read out’ of the information they contain.

Instead, experiencing a world, and a self, are inherently creative acts, the results of an active process that comes mainly from the top down rather than the bottom up. In my research as a neuroscientist – and as I explore in my new book Being You – I’ve come to view the brain as a kind of prediction machine, always in the business of making predictions about what’s out there in the world (or in here, in the body) and using sensory signals to calibrate these predictions. What we experience, in this view, is not a read out of the sensory signals, it is the content of the predictions – the brain’s best guess of what’s going on. We live in a ‘controlled hallucination’, a creative construction that remains tied to reality by a dance of top-down brain-based prediction and bottom-up sensory prediction error – but which is never, and can never be, identical with that reality.

One striking consequence of this view is that, since we all have different brains, we will all live in different subjective worlds, even when we share the same objective reality. This means the blue sky I experience on a sunny day could be different to the blue sky you’d experience, even if you were standing right next to me. And it’s likely we’d never realise this, because differences like these are by their nature private, subjective and disguised by our use of a common language.

Somehow, we expect our perceptual experiences of a shared world to be the same – for a blue sky to look the same blue to all of us

The propensity to have different experiences in a shared situation is bread-and-butter in our wider culture. No two people in the audience of a Shakespeare play, or gazing at a Rothko, will think or feel the same way. And nobody would expect them to. But, somehow, we do expect our perceptual experiences of a shared world to be the same – for a blue sky to look the same blue to all of us. That this isn’t the case is captured by what I call ‘perceptual diversity’: just as we all differ on the outside, we all differ on the inside too.

Sometimes these perceptual differences do rise to the surface. A few years ago, a poorly exposed photograph of a dress caused a social media storm because half the world saw it as being white and gold, while the other half saw it as being blue and black (it was, in fact, blue and black). This example of psychology in the wild was fascinating not only for the individual differences in colour perception that it revealed, but for the doggedness with which people clung to their way of seeing things, denying that any other way could even be possible. To my mind this rejection of alternative ways-of-seeing is rooted in the very nature of perceptual experience, which is to make it seem like the world we experience is independent of our brains and minds, even when we know that it isn’t. As Cézanne once said, colour is where the brain and the universe meet.

Perceptual diversity has come to the fore in an exciting new art-science collaboration I’ve been involved with called Dreamachine, created and produced by Collective Act – the central offer of which is a collective, immersive experience based on a little-known invention by the beat generation artist Brion Gysin and on the research of the pioneering British neuroscientist William Grey Walter.

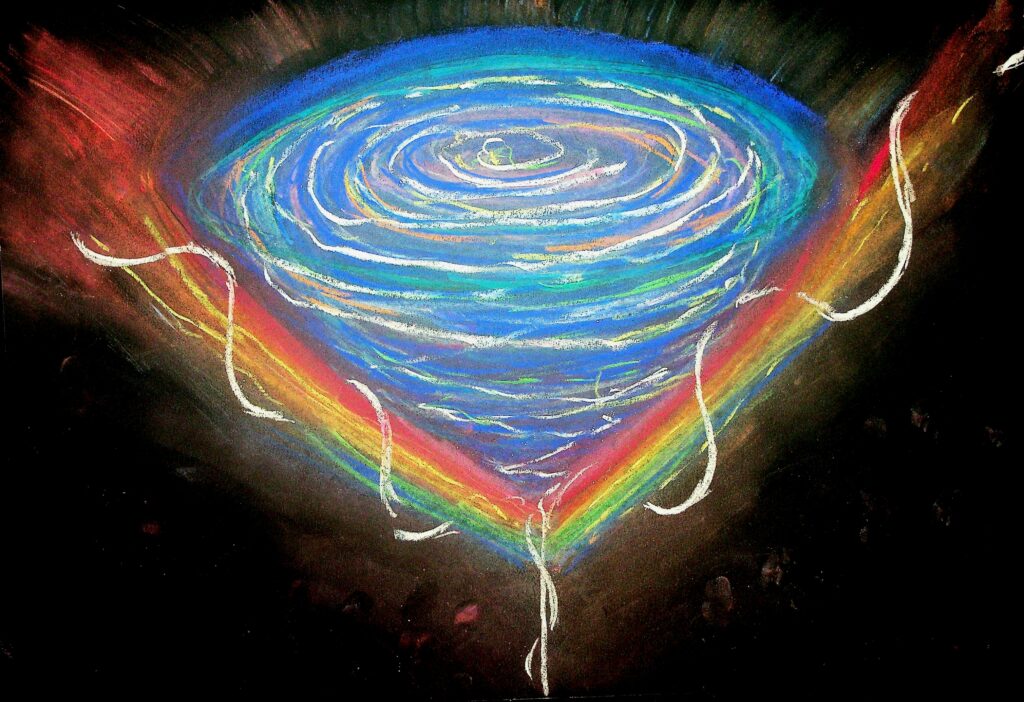

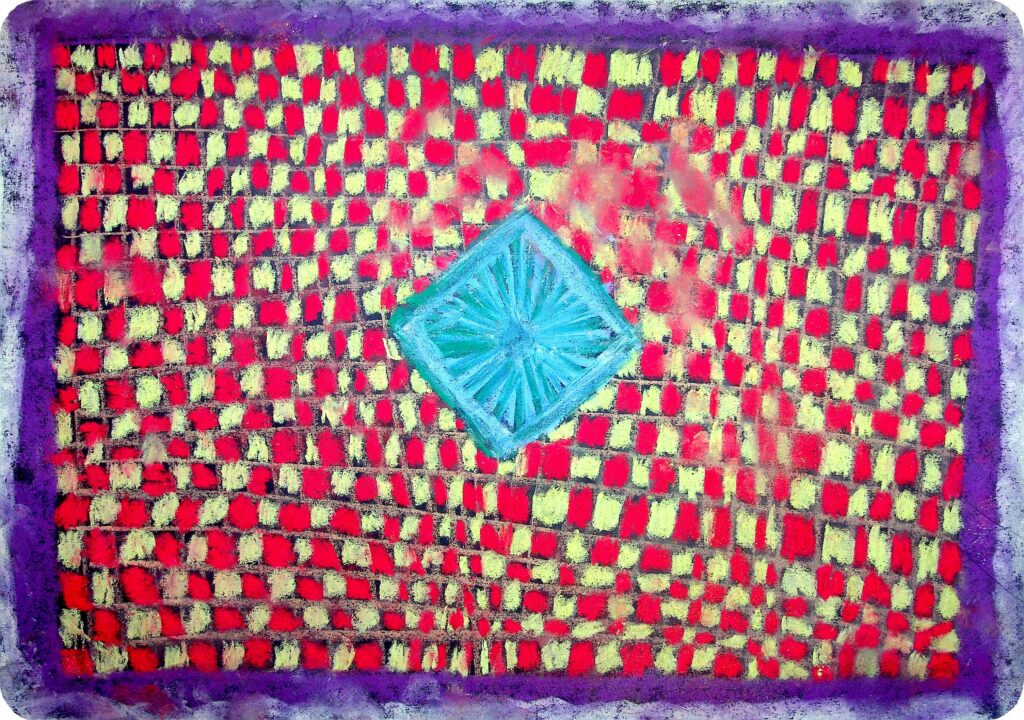

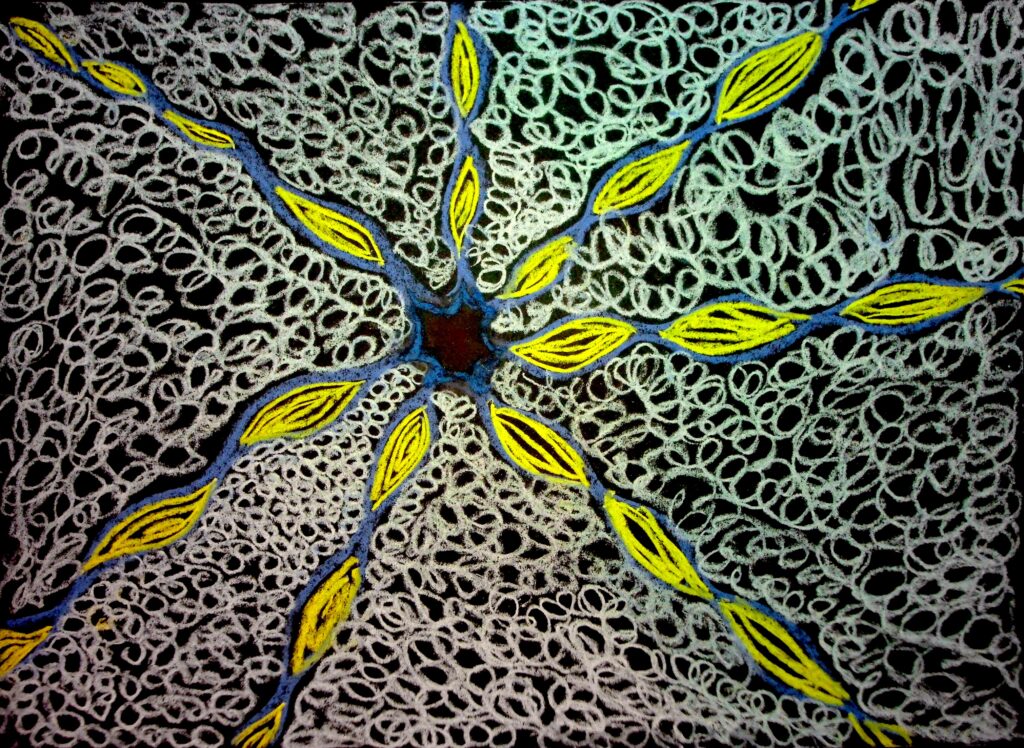

Dreamachine uses stroboscopic lighting and spatial sound to create vivid experiences of colours, shapes, movement – and frequently much more – in the minds of participants, all of whom have their eyes closed. Unlike our everyday experiences of the world around us, what arises in the mind in the Dreamachine seems to come from within, and everyone has a unique experience even though each person is exposed to exactly the same flickering white light. The drawings that people create after their journeys give an indication of this wild diversity, and they are beautiful too, even though no drawing can fully capture what the Dreamachine allows to unfold.

Another part of the Dreamachine programme takes the idea of perceptual diversity much further, in the form of a large-scale citizen science experiment called The Perception Census. Developed by a team of scientists, philosophers and experience designers, it seeks to map out – for the first time – the unique ways in which we each experience the world around us. Not just in the Dreamachine, and not just when looking at an image of a dress – but everywhere, all the time.

The Census itself consists of a series of engaging, fun, easy and quick-to-complete online experiments and interactive illusions. As well as contributing valuable data, participants will have the chance to learn about their own powers of perception and how they relate to others. Importantly, the Census goes beyond visual perception to explore many different aspects of how we experience the world, including our perception of sound and music, of the passing of time, and even of our emotions.

What will we learn from The Perception Census? To a large extent, this depends on how many people take part – tens of thousands have already engaged from over 100 countries. We’re hoping the scale of the data will bring to light many new things about human minds and brains and open up entirely new landscapes for further of research.

Whatever the data reveals, the concept of perceptual diversity has sociocultural as well as scientific value. Differences are not deficits, whether they are externally apparent differences or internal differences in our perceptual worlds. And perceptual diversity applies to all of us, not just to the variety of conditions that are associated with the existing label of ‘neurodivergence’.

My hope is that a greater appreciation of perceptual diversity will help each of us cultivate a new humility towards our own experiences, recognising that the way we see things might not be the way they are – and might be different too from the way others see the same things. And that this humility can provide new platforms for empathy, understanding and communication between people who may have very different views, both in terms of what they believe and, more literally, in terms of what they see.

A deep dive into perception – whether through the Dreamachine, The Perception Census, or any other invitation into the magic of the mind and brain – can help all of us rediscover something of the wonder of being human. The wonder that arises when we no longer take our worlds, or ourselves, for granted. Science, after all, is part of culture, sharing with the arts a creative curiosity about the human condition, our relation to others and our place in the universe. The way I see things, it’s precisely at the ever-evolving interface between science, art and technology that this creative curiosity can and will best flourish.